I’ve never been much of a sports guy. I like the idea of sports, but the actual thing has never held my attention. Watching sports casually can be fun, but I have never been able to become a fan, to become devoted to a team or player long-term. It just doesn’t feel important enough to me.

Earlier this summer, I reviewed Matthew B. Crawford’s excellent homage to cars, motor sports, and the mechanical arts, Why We Drive: Toward a Philosophy of the Open Road. In my review, I said that, as a result of reading this book, I was intending to view a sport I’d never seen before: the demolition derby.

This last weekend, I made good on that intention. My children, my brother-in-law and some of his children, a friend and some of his, and I all made our way to the demolition derby at the Dakota County Fair. I expected to enjoy it, but I enjoyed it far more than I expected. I want to return to Crawford’s book now and reflect a little on my experience at the demolition derby, in light of his book and some others.

For those who don’t know, a demolition derby is a sport (an event?) in which cars or trucks are deliberately driven into one another with the goal of disabling the other cars. Each driver aims to have his (or her!) car being the last operational vehicle in the event. The cars have been modified in various ways to facilitate this activity with some modicum of safety: all glass is removed, fuel tanks are relocated into the back seat, exhaust is redirected through pipes coming out of the hood, bars are sometimes welded on around the car, etc. A few firefighters are standing by to put out the inevitable fires. (At the derby we attended, the rules were that each car was allowed one fire, but if your car caught fire twice, you were disqualified. Forklifts are positioned just outside the area to quickly remove such cars.) The derby takes place in a large, dirt (or mud) filled arena surrounded by bleachers. Since the arena is not that big, and is full of mud, the cars can’t go all that fast, but it’s still pretty exciting when they make a good hit—especially when two cars hit a third car from opposite sides! Steam pours from smashed radiators, tires pop, and bumpers are torn from cars, but they drive on! Vehicles compete in various classes: classic cars, '80s cars, etc. While all cars but one are disabled in each event (we saw five events during the evening), most are later fixed up to some extent and re-used in other derbies. The winner of one event said he had been driving the same car in derbies for eight years.

From his book, Crawford (like me) clearly enjoyed his time at the derby, but he’s a little hard pressed to explain the enjoyment of the event:

Well-adjusted people are sometimes drawn to this sort of spectacle, but may have a hard time saying why. Of course, there is an easy and respectable thing to say, namely that a contest like this serves as an “outlet” for energies that might otherwise find more destructive release. But to say this is to absorb the demolition derby into the cosmos of the responsible, and thereby invert the meaning it evidently has for its participants. What it seems to offer them is the sheer, Dionysian joy of destruction. (Why We Drive, p.187)

Intellectuals and urbanites (I guess I’m both) tend to need to explain activities they don’t normally attend—especially those frequented by people seen as backward, as rural people often are by intellectuals and urbanites—in terms of some goal over and above that activity, especially if that goal is a psychological benefit. (Actually, most people nowadays have this need to explain all activities in terms of some psychological benefit, or some other utility, distinct from the activity itself.) From a certain frame of mind, it’s not clear why you would want to spend time watching people smash cars into each other (or smash the cars yourself). Similar incredulity is raised towards boxing, American football, fox hunting, etc.

What, then, is the value of the demolition derby? Is what it offers just the “sheer, Dionysian joy of destruction”? Is its primary value psychological? In other words, is watching (or participating in) this sport primarily valuable for the experiences it yields, whether those be pleasurable feelings or moral virtues or some other conscious effect?

While I’m not a sports fan, Susanna is a baseball fan. She has reflected elsewhere on the value of baseball, but many of her conclusions are applicable to sports in general. She says that the value of baseball is that it is an activity of leisure and contemplation:

There is a certain purity of baseball when it is played for leisure, when the fans come out in an evening or on a leisurely weekend afternoon, ready to take in a ball game, whatever comes. There is leisure in the very rhythm of the game through the repetitive sound of the ball hitting the catcher’s glove, the umpire’s voice ringing out with “strike,” or the crack of the bat and the dash to first base. There is the practiced routine grounder, the loping fly ball, the quickly turned 6-4-3 double play, and the well-pitched one-two-three inning. The fielders attentive in the field, ready for what might come. The batter poised in the box with two eyes on the ball. All of these have potential to be restorative like true leisure. At its best, the playing and viewing of baseball is a leisurely experience, akin to contemplation, and at its worst, it becomes a place of idleness and utility.

Ideally, one plays or watches sports because they are worthwhile and enjoyable in themselves. The primary value of sports is not that it helps you grow in moral virtue or a sense of community, or that it stimulates or affords an outlet for certain emotions. Sports are beautiful in their own right—that is, the excellent game is an ordered, self-revealing whole that is enjoyable for its own sake. One just enjoys contemplating them in a leisurely way. Leisure activities are not mindless; they engage the whole person, mind and body, but are enjoyable and worthwhile for their own sake, not for the sake of results or private gain. They are worthwhile because they are beautiful. When they’re done with friends on a radiant summer evening, that’s just about perfect. (It’s about baseball, not demolition derbies, but this article, the loveliest thing The Onion ever published, captures that mood with poignant wit.)

I was reminded of all this not just during the demolition derby, but while watching the Olympics during the last few weeks. (It’s only during the Olympics that I watch sports with any regularity; my family and I watched them pretty much every evening for the last two weeks, gathered around a laptop. We don’t own a TV.) What I love about the Olympics is not who wins or loses—not the stats or the medal counts—but the sheer artistry, the beauty of seeing human persons who fully embody a skill, whose bodies and minds are clearly entirely integrated, at least in the context of performing that skill. The great athletes have a total intellectual grasp on their surroundings, and they have completely joined their intellects to their senses and their other bodily abilities as they engage in their sport.

Now, I’m not sure that those competing in demolition derbies count as great athletes. But the enjoyment of the derby does come in large part from contemplating excellent, skilled performance, which joins mind and body. The competitor in a demolition derby must have excellent knowledge of his car; he has spent a long time working on it and modifying it and knows intuitively how to drive it under adverse conditions. He must quickly and intuitively grasp and respond to his surroundings. The integration of mind, body, and externals (like the car) into a single activity appears beautiful, worth contemplating.

Too often nowadays, sports, like everything else, are reduced to information. One learns players’ stats, one analyzes every aspect of play in terms of numerical measurement in order to optimize outcomes. Leisure is replaced with utilitarian calculations, intellectual intuition is set aside for rationalistic analysis. I’ve been reading a lot of Byung-Chul Han’s books lately (most recently, Non-Things); he’s probably the most perceptive social critic writing today. Like Crawford, he laments the replacement of activities in which we engage with the sheer materiality of things—which are resistant to our wills, having a sort of life of their own—with an attitude toward life in which we see everything as manipulable, as docile to our wills, so long as we have the right data, the optimal information.

The demolition derby is an encounter with sheer materiality. Steel crashes against steel and concrete, the smell of burning radiator fluid fills the air, smoke obscures one’s vision. The whole thing happens at a county fair, so there are the smells of animals, fried food, low-quality beer all around you. It’s not corporatized, not done in a slick venue. (In that respect, it’s like the Minnesota Townball version of baseball my family and I much prefer to Major League Baseball.) For both the drivers and the spectators, it’s a joyous encounter with our bodiliness, and with the way in which material things (and other embodied persons) are both shaped by and resistant to our minds and wills.

Now, Crawford is certainly right that the destruction is a big part of the fun of the derby. But that shouldn’t be understood and meaning that one goes to the derby just to stimulate the feelings that come from watching destruction, or to give vent to pent-up desires for violence. Rather, the appreciation of skilled destruction is an integral part of the leisure of watching this sport. Being an animal, bodily being requires (at least in a fallen world) destruction: we must kill to eat, we must enter into conflict with the recalcitrant material things around us to make use of them, we must destroy material things to offer fitting sacrificial worship to God. The person who laments this, who refuses to participate in rightly ordered destruction, cannot become a fulfilled human person. The derby is a celebration of both the creativity (in both the modifying and the driving of the cars) and the destruction that are crucial parts of human life. As I have said already, it is an integrating of the mind with the physical world in which we actually live.

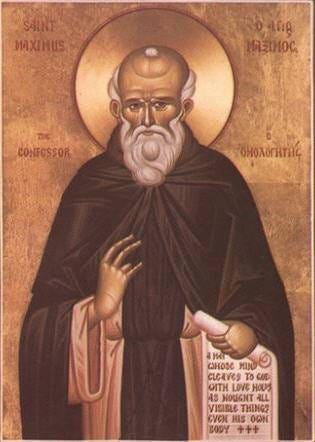

St. Maximus the Confessor, building on the Platonic tradition, describes how the human person’s full actualization requires both pleasure and frenzy, the fulfillment of those feelings (sometimes called thumos or irascible appetites or incensiveness) that are aroused when we encounter evils difficult to overcome or goods difficult to attain, feelings like fear, hope, anger, and daring. Unlike some Christian thinkers (say, St. Thomas Aquinas or Francisco Suárez or David Bentley Hart), who saw our ultimate emotional state as ideally just involving peaceful joy and pleasure, Maximus (like St. Francis de Sales) sees our best emotional state as intensifying these difficult emotions too:

Pleasure has been defined as desire realized, since pleasure presupposes the actual presence of something regarded as good. Desire, on the other hand, is pleasure that is only potential, since desire seeks the realization in the future of something regarded as good. Incensiveness is frenzy premeditated, and frenzy is incensiveness brought into action. Thus he who has subjected desire and incensiveness to the intelligence will find that his desire is changed into pleasure through his soul’s unsullied union in grace with the divine, and that his incensiveness is changed into a pure fervor shielding his pleasure in the divine, and into a self-possessed frenzy in which the soul, ravished by longing, is totally rapt in ecstasy above the realm of created beings. But so long as the world and the soul’s willing attachment to material things are alive in us, we must not give freedom to desire and incensiveness, lest they commingle with the sensible objects that are cognate to them, and make war against the soul, taking it captive with the passions, as in ancient times the Babylonians took Jerusalem. (This text, ultimately from the Responses to Thalassios, is taken from the Third Century of Various Texts, n.56, in The Philokalia, Volume 2, p.224).

We must not give free reign to our difficult and fervent emotions, letting them respond to material things without intellectual guidance. We should also not reduce sports to merely being an opportunity to discipline our emotions. But in the leisure of sport, those emotions do in fact become guided in a way centered around contemplation of beauty. The awesomeness of a good hit between two cars in the derby is a form of beauty. Just as the drivers in a derby must integrate mind and body, so likewise the spectators are led into frenzied feelings in a response to a particular form of beauty, the beauty of a well-timed collision or of a desperate swerve to avoid being hit.

The frenzy of the derby, while not yet virtuous, is nevertheless a foretaste of fulfilled, intellectually guided emotion, because it is a response to beauty. Yet this is no moralistic exercise: it is an experience of fulfilling feelings that is frenzied and fervent—in short, a lot of fun. Contemplation and leisure need not be placid; they can—perhaps they should—be intense and ecstatic. That’s an aspect of the life of virtue that we’d do well to remember, as Maximus is telling us in this passage, and as the demolition derby reminded me.

I suppose I should stop this inquiry at some point. When intellectuals start analyzing something that’s really just supposed to be enjoyed, it can get a little ridiculous. (A friend recently read a poem of his to me that started something like “I hate watching movies with my intellectually minded friends” and then went on to complain about how we over-analyze everything; he said this poem was dedicated to me.) But I do think there’s something important about the demolition derby, and about sport in general, that points to the human person’s naturally leisurely, contemplative nature, and to the proper place of intense emotion in that leisure. While I was at the derby, I didn’t analyze or theorize; I just enjoyed it: the excitement of the event against the background of the fair—the rides, the animals, my fellow citizens of Dakota County—and the beauty of a summer night.