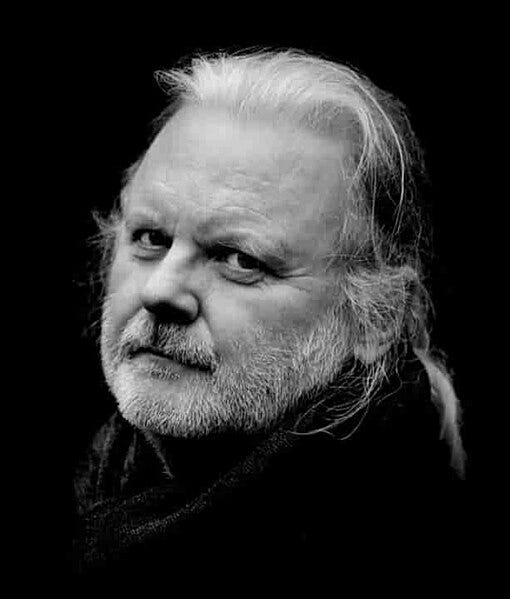

I hadn’t heard of Jon Fosse until he won the Nobel Prize in Literature last year. But upon hearing him described as a writer who took spiritual and existential themes seriously, whose style was similar to Samuel Beckett’s, and who was a recent convert to Catholicism, I knew I needed to check out his writing. I immediately read his masterpiece novel, Septology (published in English in three parts, The Other Name, I is Another, and A New Name), and I’ve since read his novellae A Shining and Aliss at the Fire. He’s quickly become one of my favorite writers of fiction.

Fosse is a great pleasure to read because he is clearly deeply committed to the craft of writing. One thing I want out of a work of art is excellent form. (For novels, my gold standard is Henry James.) Regardless of the content or the subject matter, a work of art should be well structured. Artistic beauty requires a pleasing and proportionate arrangement of parts—proportioned to each other and to the whole, and a form that fits with and complements the content. Here, Fosse delivers in unexpected ways. Septology is written basically as one continuous sentence; at least, there are no periods. In this, it hearkens to Joyce and Faulkner. But it is never obscure in its stream of consciousness; the literary style never feels like a gimmick. There is a perfect union of form and content. The traditional novel, with its elements of plot and character study and ordinary events exposed for our inspection, is perfectly joined to the styles of high modernism and post-modernism. In accomplishing this synthesis, this is clearly a new stage in the history of writing novels.

Furthermore, I don’t think I’ve ever related to a character more than I connected to Asle, the main character of Septology. The book is an account of a few weeks in his life, including his memories of his earlier life. Asle is an aging painter, widower, and convert to Catholicism who lives alone on the coast of Norway. We hear Asle’s interior monologue as he paints, as he spends time with his neighbor and other people, as he travels into the city to visit the gallery that exhibits his paintings, and as he prays. But I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a character that exhibits the strange mix of great faith and extreme doubt, pious devotion and wild theological speculation, sense for the presence of God and sense for the meaninglessness of reality that has been my relatively constant experience of life. Likewise, Asle’s intense love and longing for his wife and for art are my experience too, as is his simultaneous longing for people and for solitude, and his clear sense of vocation to do one thing (in his case, painting; in mine, philosophy) combined with a sense of deep confusion about his own actions and the actions of others.

What I want to focus on here, though, is an idea that runs through the whole book, an idea that shows up in Asle’s thinking about his paintings, but also his thinking about God. While Asle painted realistic pictures when he was younger, at the time of the novel, his paintings are described as having a high degree of abstraction, though they are still, perhaps, representational. (The main painting described in the book is one of a “St. Andrew’s Cross”, an x-shaped cross, this one composed of a single brown and a single purple line that cross in the middle of the canvas.) Asle often talks about how he has one picture deep within himself, and all of his paintings are facets of that inner picture. He has a need to externalize these pictures, to get them out of himself into the world. But a quality he thinks all his paintings need to have is “shining darkness.” To get a sense for this idea, it’s worth reading a few passages from the book:

…still it’s probably these moments when I’m sitting and staring into empty nothingness, and becoming empty, becoming still, that are my deepest truest prayers, and once I get into the empty stillness I can stay there for a long time, sit like that for a long time, and I don’t even realize I’m sitting there, I just sit and stare into the empty nothingness I’m looking at, I can sit like that for I don’t know how long but it’s a long, long time, and I believe these silent moments enter into the light in my paintings, the light that is clearest in darkness, yes, the shining darkness, I don’t know for sure but that’s what I think, or hope, that it might be like that… (The Other Name, p. 258)

…what I want to show to other people has to do with light, or with darkness, it has to do with the shining darkness full as it is of nothingness, yes, it’s possible to think that way, to use such words… (The Other Name, p.265)

…maybe it’s a strange habit, always wanting to look at my paintings in the dark, yes, I can even paint in the dark, because something happens to a picture in the dark, yes, the colours disappear in a way but in another way they become clearer, the shining darkness that I’m always trying to paint is visible in the darkness, yes, the darker it is the clearer whatever invisibly shines in a picture is, and it can shine from so many kinds of colour but it’s usually form the dark colours, yes, especially form black, I think and I think that when I went to the Art School they said you should never paint with black because it’s not a colour, they said, but black, yes, how could I ever have painted my pictures without black? no, I don’t understand it, because it’s in the darkness that God lives, yes, God is darkness, and that darkness, God’s darkness, yes, that nothingness, yes, it shines, it’s from God’s darkness that the light comes, the invisible light… (The Other Name, p.410)

…I think that God is so far away that no one can say anything about him and that’s why all ideas about God are wrong, and at the same time he is so close that we almost can’t notice him, because he is the foundation in a person, or the abyss, you can call it whatever you want, I think and I often think about the picture that’s kind of innermost inside me, and it’s good and bad equally, it doesn’t matter what you call it, or I think about God’s shining darkness inside me, a darkness that’s also a light, and that’s also nothing, that is not a thing, I think and we come from God and go back to God, I think and I think that now I need to stop with these thoughts of mine, they don’t go anywhere… (A New Name, p.78)

There are many, many other cases of this idea in the book. It is in darkness, in obscurity, in emptiness and nothingness, in suffering, in the Cross and the descent into hell, that God reveals Himself. The book is full of accounts of the most profound—yet entirely ordinary—sufferings, and yet all of that suffering (the sins, addictions, illnesses, heartbreaks, cruelties, dark nights of faith, and so on) is made, under Fosse’s hands to shine. There is an ineffable quality of radiance, of someone mutely but definitely present and showing himself in the midst of the darkness.

It’s been that way in my own life, as in the lives of many others. When I am most in doubt, when my wife or children have had terrible, long-term illnesses or injuries, when friends have suddenly died, when the scandals in the Church or our country are overwhelming—it is then that there always shines forth that uncanny, comforting, commanding, shining presence. It’s true that “God is light, and in him is no darkness at all” (1 John 1:5), but also God is a God “that hides” himself (Isaiah 45:15), and the horror of the Cross just is the glory with which the Father glorified the Son “at once” (John 13:32), the glory of ineffable love made present in, appearing in, the deepest darkness. Meister Eckhart, who is quoted a few times in Fosse’s book, helps us see why God (must?) reveals Himself in this way:

Note that it is of the nature of light that its transparency is never seen and does not appear to shine unless something dark, such as pitch or lead or the like, is added to it. “God is light, and there is no darkness in Him.” That is what is expressed here—“The light shines in the darkness,” that is, in creatures that have something dark (i.e., nothingness) added to them. This is what Dionysius says: “The divine ray cannot illumine us save as hidden beneath many veils.” In the same way, fire in itself, in its sphere, does not give light. Hence it is called darkness in Genesis 1:2, “Darkness (that is, fire, according to the doctors) was on the face of the abyss.” Fire does give light in foreign material, such as in anything earthly, like coal, or in a flame in air. (Commentary on the Gospel of St. John, n.74)

What’s remarkable about Fosse is that he shows us that there is a definite analogy between the shining darkness of the crucifixions we all undergo, even in our banal and bourgeois lives, and the shining darkness that can be depicted in art. By looking at (or reading, or listening to) art that is at once dark and obscure and invisibly and interiorly luminous, I both directly encounter the presence of a depth, of that which is entirely other than the world of finite things and have my perception trained to see the presence of that depth, that Other (which is also, because innermost to all things, Not-Other), in the darkest moments of my actual life. What a remarkable and strange thing that there should be this direct, perceivable connection between certain arrangements of black paint and the pain of seeing my wife (or, in the novel, Asle seeing his wife) suffer with a terrible illness!

The truth of Fosse’s account of the shining darkness was abundantly revealed to me while I was reading Septology when I visited the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas. I had wanted to visit that Chapel for many years, since I read about it in Jean-Luc Marion’s In Excess in graduate school. Rothko, an abstract expressionist painter, is famous for his huge canvases which present luminous blocks of color, laid down on his canvases in many thin layers, so that they appear to have great depth. The canvases in the Chapel are masses of black, brown, and dark purple, but mostly black. The chapel itself is a fine piece of modernist architecture, and inside it is utterly silent, with subdued lighting. You are meant to view the canvases from up close, to let the vast surface of darkness fill your field of vision completely. What you see are shimmering veils of night, waves and cascades of darkness, endless depths of silence. What you receive in looking at them is an extraordinary peace. You are surrounded by these mute presences, these great dark paintings, like some primordial shrine, like ancient standing stones. Despite the utter lack of representation, there is an overwhelming sense of the importance of what you are seeing.

Christian theologians and philosophers like Thomas Hibbs and Jeremy Begbie have a sort of appreciation for this kind of art, but they also worry about it. It inculcates helpful attitudes of self-emptying, they think, but they worry that it is nihilistic, iconoclastic, rejecting Logos (form, meaning, name) in favor of nothingness and emptiness. (When I went to see the Chapel, I was attending a Catholic philosophy conference; when I returned from the Chapel, one of my friends and colleagues derisively asked me if I had enjoyed the “Buddhist nihilism.” I said I certainly had!) They worry that the “divine” with which this art puts us in touch is not the personal God of Christianity, revealed in the Incarnation, with its definite form, as a loving Trinity of persons, but an amorphous, impersonal transcendence. Rather than Rothko’s unflinching stare into the abyss, they prefer the Christian abstract but quasi-representational expressionism of Makoto Fujimura.

Jon Fosse helps us see just how unfounded those worries are—but also, through his characters’ reflections, we can see how the dark, nameless, abyssal paintings of someone like Rothko are preferable for Christians to the apologetic, didactic, bright (but almost superficial, even, one might worry, kitschy) expressionism of Fujimura. (A much better explicitly Christian analogue to Rothko’s art is the painting of William Congdon.) Traditional theology tells us we must first affirm of God various claims—like that He is good or that He is light. But then, since we tend to understand terms like ‘good’ or ‘light’ just in the way that they apply to creatures, we must make the step of negative theology, and deny these things of God: God is not good, God is not light. And then, having been purified by negation, we come to see that God is each of these perfections (like goodness or light), but in a way infinitely more excellent than how they belong to creatures. Fosse and Rothko help us to experience all three of these steps simultaneously: negation (darkness) and affirmation (shining) at the same time. Named, shiny, chipper art cannot do this.

The shining darkness that Rothko depicts (or that Asle depicts in his paintings in the novel) is a revelation of the shining darkness at the foundation of every human heart. That darkness can be encountered as an amorphous abyss, a sheer nothingness. It can lead, as it did for Rothko, to despair and suicide—that is the risk of faith, which is not a smooth road, but a narrow way, difficult to find. But it need not appear that way, and, indeed, that is not the way it appears when it is best perceived. Fosse at one point quotes the opening lines of Hölderlin’s “Patmos”:

Near is And difficult to grasp, the God. But where danger threatens That which saves from it also grows.

To encounter God, to find Him present in the darkest of nights, is not an event that we should encounter in an entirely cheerful way. Bright surfaces do indeed convey something about God, but so does immersion in night and nothingness. Nothingness can appear (as it did for philosophers like Nishida Kitaro or mystics like Meister Eckhart) as the very foundation of personal reality. Looked at rightly, the shining darkness is a personal presence, one that is illumined by the beliefs of faith and itself better reveals the content of those beliefs to us. This is not to say that one can or should automatically arrive at the doctrines of the Trinity or the Incarnation just by looking at Rothko’s dark paintings. But it is to say that there is in fact a presence of the personal God in those paintings, and that this can be seen, by those with eyes to see.

…the resurrection of God, and with his disappearing from the created world a new connection between God and humanity was formed, but not in this world, or rather it was like an annihilation of this world, it was like in opposition to this world that the good Lord now existed in humanity, yes, like a shining darkness deep inside people, yes, maybe you can think of it as like The Holy Spirit… (A New Name, p.81-82)

Once you see the shining darkness in one piece of art, you begin to see it elsewhere too. Soon after I finished reading Septology, I first heard the music of the contemporary Icelandic composer Anna Þorvaldsdóttir. As Rothko’s paintings are dense with shimmering, incomprehensible, weighty veils of darkness, so Þorvaldsdóttir’s music is dense with dark and dissonant and weighty instrumentation, like heavy curtains of sound dropped upon the listener. It is (quite deliberately) evocative of geological processes, of great weights and masses of time and stone and the depths of interstellar space. You can see the shining darkness in Rothko, and you can hear it in Þorvaldsdóttir. (Actually, I think Þorvaldsdóttir’s music is a better commentary on Rothko’s paintings—though it isn’t trying to be—than the piece actually inspired by the Chapel, by Morton Feldman.) As Fosse’s paintings are a remarkable synthesis of the traditional and the modernist novel, so Þorvaldsdóttir’s music is a synthesis of classical orchestration with post-modernist timbres. Listening to Þorvaldsdóttir’s music in light of what I had read in Fosse and in light of my experience beholding the shining darkness in the Rothko Chapel, I realized that what I love about many instances of music and painting that are not beloved by many of my fellow Christians is its ability to make present that quality of shining darkness. I find that same quality, for example, in the music of the Revolutionary Army of the Infant Jesus or the Mount Fuji Doomjazz Corporation.

To show us the shining darkness, the invisible in the visible, the simultaneity of affirmation and negation—that is among the highest vocations of art. What an extraordinary thing that we, by the humble arrangement of word or paint or sound can evoke the presence, the radiant no-thing-ness at the heart of all things! And what an extraordinary thing that the artist does this (contrary to proud romanticism) not by being a sort of confident demi-god (in Septology, Asle spends his life in almost complete confusion, pulled along by events outside his control) but by entering into the depths of humility, by living out of the shining darkness that lives in each of our hearts.