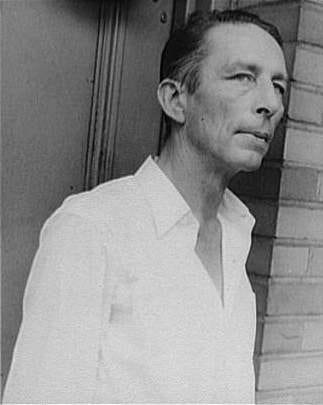

So far as I can remember, I first encountered the work of the poet Robinson Jeffers while reading Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age in graduate school. Taylor introduces Jeffers while reflecting on the human propensity to violence. Jeffers was the great mid-20th century poet of the California Big Sur coast, the poet of hard rocks and hard, violent ranchers, of lonely shores and lonely, tragic women, of hawks and hunting pelicans over the waves. He’s a deeply religious poet, though not a Christian one. His poetry is suffused with what Susanna called, in her post a few weeks ago, the sacramentality of nature. A sacrament is a sign that makes present what it signifies; the beauty of nature, on Jeffers’ telling, makes God present more than anything else does.

His God, though, is not merciful or moral or an intelligent designer: rather, He is the one Who watches the beauty of all things, from pelicans to airplanes; He is the one Who longs for beauty, and Who pursues that beauty through enduring violence and suffering. I mentioned Jeffers a few weeks ago when reflecting on the view of nature in Moby-Dick; here, I want to build on both that earlier post of mine and Susanna’s reflections on the sacramentality of nature.

What is great about human beings, for Jeffers, is that we can turn away from human concerns, and, like God, contemplate the beauty of the whole cosmos. For Taylor, Jeffers is a thinker who takes seriously—more seriously than many Christians—the human drive to violence, and who offers an alternative, modern religious vision. In the same vein as Georges Bataille and Friedrich Nietzsche, Jeffers’ hard, violent, beautiful pantheism is a way to take seriously both the glory of nature and the religious heritages of humankind, while leaving behind the all-too-human concerns of Christianity. Like Byung-Chul Han, the philosopher whose books I reviewed last week, Jeffers offers a contemplative vision, albeit in an impersonal vein.

Upon reading those three or four pages about Jeffers in Taylor in graduate school, I was utterly fascinated. I immediately read The Women at Point Sur, and in the thirteen years or so since then, I have read lots of Jeffers’ poetry. When I was out in San Francisco for a conference a while back, I cut out of part of the conference and rented a car so that I could make a pilgrimage to the rock house and tower that Jeffers built in Carmel-By-The-Sea. (Jeffers settled there before Carmel was an ultra-expensive neighborhood, when it was just a craggy, windswept shore.) On a family trip a few years later—the trip to the California coast that Susanna mentioned in her post a few weeks ago—we swung by Hawk Tower again so that the whole family could see it. And I’ve continued to read Jeffers’ poetry quite frequently, and literature on Jeffers. In the last couple weeks, for example, I read a biography, James Karman’s Robinson Jeffers: Poet and Prophet.

Why do we want to spend time in harsh and empty natural places, in howling deserts and on precipitous shores? Susanna explored the sacramentality of nature in connection to the writing of Annie Dillard—how nature reveals God’s creativity, presence, and excess. Dillard too, like Melville and Jeffers, like many American lovers of nature, is attentive to the weird juxtaposition of beauty and violence in the nature world. These are themes we talk about a lot in our house, both in light of our reading, which often intersects with the American Nature Writing tradition, and in light of our frequent hikes and camping trips. When one is in forest or desert, prairie or mountain range, one feels oneself taken up into a greater whole, a whole that is different from the human world, with its own uncanny concerns. A few hours—sometimes, just a few minutes—in nature are enough to remove one’s attention from oneself and transfer it onto what is other than oneself. To gaze at a forest is both healing (it takes your attention off your egotistical concerns and transfers it onto what is alive and good without human worry) and unsettling (the trees, as J.R.R. Tolkien saw, don’t care about you; indeed, they may even be hostile to you).

While sitting in camp, it's easy to be romantic about nature, to forget its harshness and its lack of care for human concerns. While enjoying the solace of woods and waves, it’s easy to forget how pelicans devour fish, or how hawks rend their prey, or how we—who are part of nature no less than the birds and the fish—inflict violence upon one another. Jeffers never lets you forget those things. His poetry, like ancient Greek myth, is drenched in rape and murder, jealousy and hatred. But over it all, there reigns a supreme peace, the peace of beauty which binds all things together in a shining whole. Jeffers’ own life, as Karman shows in his biography, was full of tension and self-inflicted hardship—abuse, affairs, political rancor. He was full of complications: a poetry of violence coupled with his own pacifist views, a lifelong marriage that began in a scandalous affair. And yet, out of all of this, he managed to draw poetry that, for all of its frequent preachiness and sermonizing, has a stunning force and power, a pattern of stresses and images unlike anything else in modern poetry, like the incantations of ancient bards.

Why would a committed Christian want to read someone like Jeffers? Though raised by a father who was a Christian pastor, Jeffers opposed Christianity and all organized religions. He believed, again in the vein of Nietzsche, that Christ was an illegitimate child, but also a tortured and brilliant genius, who out of an obsessive longing to be loved and accepted, invented the myth of his own status as Messiah, and brought about his own death to make sure that the myth of his life lived on. Why would someone like me, who loves Jesus, care what such a person writes?

By God is meant the first cause of all things, the absolute goodness and beauty from Whom all things come, the burning heart of love at the center of the world, Who reveals Himself in all things and Who actively preserves all things. If we are going to know God, we must attend to all aspects of His self-revelation. We must see how He manifests Himself not just in the glory of sunlight and in leaves on trees, in the pretty aspects of nature, but also how He shows Himself in storm and wind, in battle and passion. Jeffers’ poetry helps show us that uncanny, absolute presence of beauty that suffuses even these terrible things. For all his misreading of the life of Christ, Jeffers does not misread nature. He clearly hears that call of beauty that comes through all things in the natural world, the pleasant and the unpleasant, that call to turn away from the ordinary things of human life to contemplate the glory of the whole cosmos.

Jeffers is immensely worthwhile for Christians to read because, as Karman intimates throughout his biography, Jeffers had the spirit and rhythms of an Old Testament prophet. He uses these prophetic gifts to defend the value of the natural environment and to oppose all the many political ideologies of the twentieth century. But he also uses these gifts to remind us of ways that God is revealed in nature—ways that are there in our tradition but that we modern Christians, sunk in a particular, often narrow, reading of the New Testament, tend to overlook. God is not just the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, but the God whose path led through the sea and no one saw His footprints. He not only is the one who feeds the alien, the widow, and the orphan, but also the one who provides prey for the ravens. He gives to men prowess and victory in battle; he made the great sea monsters to have fun. We would do well to see God not only in gentle human community, but in the desert and the whirlwind as well. Alongside the personalism of Christianity—its view that persons hold the central place in reality, and that love of persons is our highest call—we would do well (as my teacher John White noted to me long ago) to cultivate a complementary impersonalism, an appreciation for the wildness of the world, and of the God Who stands behind it, whose likeness is found in both the personal and the non-personal.

To hold this vision of God pouring Himself out through all the beauties of the world, we certainly need not share Jeffers’ pantheist view that suffering and violence are God working out His own need for beauty by torturing Himself and inflicting suffering on Himself. (Though, even—or especially—for the Christian, it is worthwhile not to just dismiss such a view, but to spend time thinking about it, reflecting upon what it gets right, what it helps us accurately see, especially about Christ, and where it falls drastically short of the truth.)

We need not even hold that God directly wills natural suffering and death, or that God originally wanted a world like this. We could, instead, follow Tolkien, whose vision, while Christian, is not all that far removed from Jeffers’. In Tolkien’s mythic vision, the world comes about through the music of the gods; evil and discord enter the world through the imaginings of the dark spirit Melkor, and yet God weaves Melkor’s discord into the music of the world that He Himself produces. So it may be in our world: the violence and harshness of the world might not have been originally intended by God, and yet God has taken these things up into His themes, His beauty: He consents to reveal Himself even through these things. As Jeffers teaches us, even in the darkness and emptiness and harshness of the world, we can find the beauty of God. May we so find it, and gaze upon it unflinchingly.

Wonderful post. I appreciate how Jeffers provides a striking, dark contrast to the glorious nature poetry of someone like Gerard Manley Hopkins. So different, and yet both so resonant.