Among the artworks on the wall of my living room is a large print of Thomas Cole’s The Arcadian or Pastoral State from his Course of Empire series of paintings. The scene depicts a verdant landscape, a peaceful village and its environs, surrounded by water and mountains, early in the morning, early in summer, early in the life of a culture. A few soldiers are riding by, but most of the people are engaged in eminently peaceful activities: a shepherd watches his flock, in the distance fields are being plowed and ships are being built, a garlanded youth and maiden dance to the music of a pipe, an old man redolent of Socrates traces geometrical figures on the ground while a boy draws a stick figure on the pavement of a bridge, smoke rises to heaven from sacrifices in a Stonehenge-like temple. It is a scene that shows the dawn of the arts, religion, philosophy, and useful crafts. When I take the time to contemplate it, it moves my soul to peace.

Lately, I’ve been reading a variety of lyrical texts from poets like Goethe, Hölderlin, and Rilke, that have brought to mind the mood that is conveyed by this painting I love so much. I thought it would be worthwhile to consider this mood—both because it is worth contemplating in itself and also because it is something we’re often missing in our current political and religious climate. It would be good for us personally, politically, and religiously to cultivate this mood.

My interest here is in the mood conveyed by Cole’s painting considered in itself, apart from its connection to the other paintings in the Course of Empire. Prior to this painting in the series, there is a depiction of the “savage state”: human beings in the wilderness, prior to the dawn of civilization. And after this painting, Cole depicted the rise, destruction, and ruin of a luxurious classically-inflected civilization. I am not interested here in those paintings, but in the mood that is specifically conveyed by The Arcadian or Pastoral State, and by certain lyric poems and other artworks.

This issue of how moods shape our perceptions, actions, and way of life is of great interest to me. In earlier posts, I described how there is a peculiar mood of autumn (evoked especially by John Keats) and a hard violent feel of predatory birds and rocky shores (masterfully expressed by Robinson Jeffers). Cole’s painting captures a distinct mood, the arcadian or pastoral mood, which is expressed well in idyllic paintings like this one or in lyrical verse or in lush music, like Joseph Canteloube’s Chants d’Auvergne. This mood is, as Dietrich von Hildebrand says, “hovering and fragrant.” It is the feel of rosy-fingered dawns and scented evenings:

The shepherd with his flock, especially with sheep or goats, has an aesthetic quality all its own. The closeness to nature, the contemplative element of his activity, the sight of the sheep with the sheepdog, their form, the peaceful, calm surroundings: all this unites to form a lovely unity that irradiates a very specific atmosphere. The loose unity of a placidly murmuring brook, a meadow, some trees, poplars, willows (including weeping willows), and a gentle hill in the background can possess an intense pastoral atmosphere.” (Hildebrand, Aesthetics, volume 1, p. 254)

Hildebrand calls such scenes poetic, but we might more specifically call them lyrical. The romantic, somewhat intoxicating feel of the early morning or the evening in late spring or early summer, with the scent of flowers, the feel of warm breezes, suffused with half-light…none of that is captured well by epic poetry or dramatic verse or novelistic prose. If this mood is going to be presented in verse, it needs a form that can be concerned with what is particular, lovely, gentle, calm, and peaceful, as well as wistful and a bit melancholic. It can be conveyed well by lyric poetry—hymns and odes and elegies. Consider, for example, the words of Friedrich Hölderlin’s “Bread and Wine,” in Michael Hamburger’s wonderful translation:

Round us the town is at rest; the street, in pale lamplight, falls quiet And, their torches ablaze, coaches rush through and away […] But faint music of strings comes drifting from gardens; it could be Someone in love who plays there, could be a man all alone Thinking of distant friends, the days of his youth; and the fountains, Ever welling and new, plash amid balm-breathing beds. Church bells ring; every stroke hangs still in the quivering half-light And the watchman calls out, mindful, no less, of the hour. Now a breeze rises too and ruffles the crests of the coppice, Look, and in secret our globe’s shadowy image, the moon, Slowly is rising too; and Night, the fantastical, comes now Full of stars […] (p.151)

Or, for a very similar feel, there is Novalis’ first of the “Hymns to the Night,” as translated by George MacDonald:

What springs up all at once so sweetly boding in my heart, and stills the soft air of sadness? Dost thou also take a pleasure in us, dark Night? What holdest thou under thy mantle, that with hidden power affects my soul? Precious balm drips from thy hand out of its bundle of poppies. Thou upliftest the heavy-laden wings of the soul. Darkly and inexpressibly are we moved--joy-startled, I see a grave face that, tender and worshipful, inclines toward me, and, amid manifold entangled locks, reveals the youthful loveliness of the Mother.

When it is persistent and recurs again and again in different people and at different times, a mood is not just a passing emotion. Rather, it is a particular way in which one can be attuned to reality. The way in which moods reveal reality was discovered and described particularly well by some of the early phenomenologists, like Max Scheler, Martin Heidegger, and St. Edith Stein. For example, an anxious mood aligns all of your thoughts and desires and perceptions with reality in such a way that you see things in reality that you wouldn’t otherwise notice, like the way in which human life and material existence as a whole inexorably rolls on to death. Likewise, a trusting mood attunes you to reality in a different way, so that you see reality as a sheltering place—of which the anxious person is blind and unaware. The lyrical or pastoral mood enables us to see and deeply feel the joy and freshness of existence, the value of the small and particular, of the tender and romantic, which cannot be captured in the sweeping tones of the epic or the cosmic drama.

What does this mood convey to us that is of religious importance? To experience the pastoral mood is already to have a sense of something more than human. To walk the scented paths of the forest, or to gaze upon the wine-dark sea, is already to be under the spell of the nymphs, to be caught up into something divine. An evocation of the spirit, a numinous presence inexpressible in prose, hovers over these scenes. The lyric mood is not one in which one is inclined to do systematic theology or apologetics or scholastic metaphysics (what Hans Urs von Balthasar calls “epic” or “dramatic” theology). But it is indispensable to a fully formed religious sensibility nonetheless. Religious life is not just theology and philosophy, nor does it just consist in the hard-edged moods of Jeffers, nor in the strenuous attitude of moral activism.

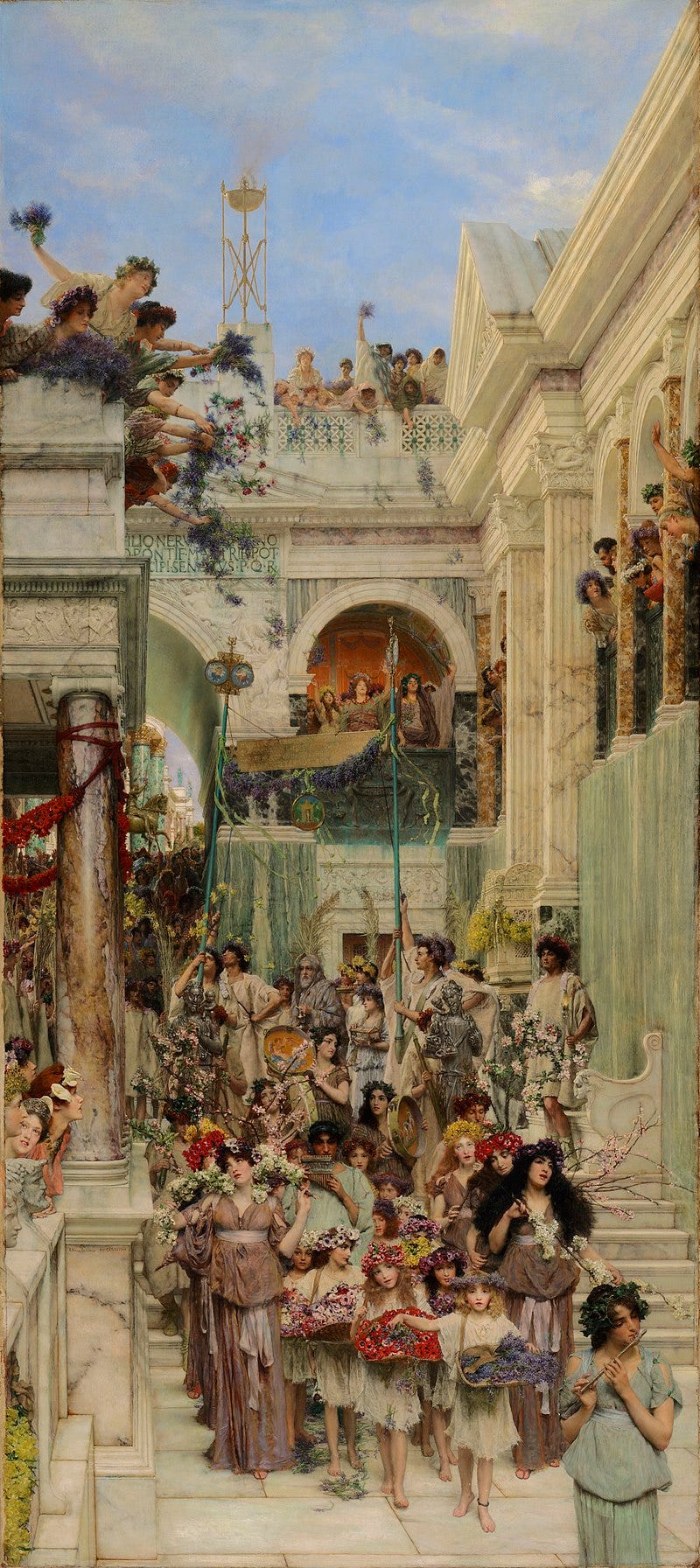

A full religious life, a full relation to the divine, includes the joy of springtime processions, the feel of romance with the divine Bridegroom, the happy solemnity of sitting down to eat at a ritual feast with God. No one saw this better than that Spanish romantic, St. John of the Cross in The Spiritual Canticle:

My Beloved, the mountains, and lonely wooded valleys strange islands, and resounding rivers, the whistling of love-stirring breezes, the tranquil night at the time of the rising dawn, silent music, sounding solitude, the supper that refreshes and deepens love. […] The bride has entered the sweet garden of her desire, and she rests in delight, laying her neck on the gentle arms of her Beloved.

But Hölderlin too felt this same mood in his visions of the banquet of the gods in Celebration of Peace:

The all-assembling, where heavenly beings are Not manifest in miracles, nor unseen in thunderstorms, But where in hymns hospitably conjoined And present in choirs, a holy number, The blessed in every way Meet and forgather, and their best-beloved, To whom they are attached is not missing; for that is why You to the banquet now prepared I called.

There are those who would dismiss this mood as nothing but an expression of adolescent naivete. To be thinking about dancing on the green with one’s lady love, or walking in splendid, flower-bedecked procession to the temple for a sacrifice, or gazing at lights over the water in the fragrant night smacks of self-absorption or of evasion of larger social responsibility. For some, the pastoral smacks of inauthentic, aristocratic play-acting: Don Quixote playing at being shepherds and knights, Marie Antoinette dressing up as a milkmaid. For others, the pastoral falsely romanticizes the rural life, ignoring its hardships and its crudities, the ways in which the hardships of the farmer’s life wears him down, the ways in which agriculture destroys the natural environment. (See, for example, John Muir’s caustic portrayal of the shepherd in My First Summer in the Sierra.) There are those who would dismiss this mood as a way to set up a falsely positive view of life, to ignore death and hardship and the oppression rampant throughout the world.

But all of this is to miss the precise contours of this mood. Et in Arcadia ego, says Death in Virgil—I, Death, am also in Arcadia, and this was understood by those who took up this theme, from Nicolas Poussin to Evelyn Waugh. There is an ineradicable melancholy to the fragrance of the lyrically poetic. Outside my house right now, the wind is howling and the snow is blowing; I am surrounded by the cold, hard death of winter, and my longing turns to the springtime, to the poetry of lilacs and new leaves. Yet even there, in the warmth and jubilation of new life, the chill of death is found. In Cole’s painting, the philosopher grows old, the priest must kill in order to sacrifice, brave but warlike soldiers patrol the roads.

To turn to the pastoral is not to evade death, to set up a sick and sentimental cult of youth and health. It is rather to be attuned to that peculiar hovering and fragrant mood that alerts us to a certain ineffable loving presence of the divine, and to be attuned to the possibilities for peace that belong to our suffering race. It does not matter whether Cole’s painting accurately portrays the pastoral life as it was actually lived: what is important is the mood it conveys, a particular stance toward the world that is a possibility for all human persons.

This brings us to the political importance of this peaceful, fragrant, romantic mood. In Plato’s Republic, before describing the city that requires virtue, Socrates describes a peaceful city, one in which everyone is content with the pastoral life, with its hovering sense of the divine, where no one overreaches or desires unnecessary luxuries:

Let us then consider, first of all, what will be their way of life, now that we have thus established them. Will they not produce corn, and wine, and clothes, and shoes, and build houses for themselves? And when they are housed, they will work, in summer, commonly, stripped and barefoot, but in winter substantially clothed and shod. They will feed on barley-meal and flour of wheat, baking and kneading them, making noble cakes and loaves; these they will serve up on a mat of reeds or on clean leaves, themselves reclining the while upon beds strewn with yew or myrtle. And they and their children will feast, drinking of the wine which they have made, wearing garlands on their heads, and hymning the praises of the gods, in happy converse with one another. And they will take care that their families do not exceed their means; having an eye to poverty or war…of course they must have a relish-salt, and olives, and cheese, and they will boil roots and herbs such as country people prepare; for a dessert we shall give them figs, and peas, and beans; and they will roast myrtle-berries and acorns at the fire, drinking in moderation. And with such a diet they may be expected to live in peace and health to a good old age, and bequeath a similar life to their children after them. (Republic II.372a-c)

Glaucon, who is in dialogue with Socrates, belittles this vision as a “city for pigs.” He wants a city in which people have luxuries and comfort; he thinks a life lived so simply is animalistic, unbefitting of free persons. When I was in graduate school, in a seminar on the Republic, I wrote a paper defending this city against Glaucon’s criticisms, the argument of which my professor dismissed somewhat mockingly. But I stand by my love for Socrates’ first, pastoral city. Like the dawning culture in Cole’s painting or the banquet in Hölderlin’s poem, Socrates holds out the possibility of a poetic, pastoral, peaceful state.

Our political life is full of the dreams of power, of having everything we want technologically, sexually, financially, and so on, with none of the drawbacks or harms that necessarily come with those luxuries. Sometimes, when the pastoral mood is upon me, I have a dream of another way to live—and that, I think, is the political value of this mood: when it comes over us, it opens our eyes to the attraction of another way to live.

I dream of a world that consists entirely of monasteries, convents, universities, and small towns and villages centered around them. There is no electricity and there are no great riches (but there are antibiotics). We spend our days in farming, crafts, artistic creativity, and intellectual pursuits. People have lots of children and love them dearly. There are many processions, and seven times a day we pause to go up to the monastery and hymn our God. Every feast day (and its octaves and seasons) is joyfully celebrated, with simple but leisurely open-air banquets whenever the weather allows, with dances and music upon the green. Every location has an ever-growing number of saints who are duly honored; in every place, people are attentive to the spirits—the nymphs or manitous or angels—that hover over woods and springs with their blessings; at every hearth, the genius or daimon of the house is celebrated. Mine is a Christian vision so there are (sadly) no animal sacrifices, but lots of incense and candles and bonfires are burned. This is not a dream of the ultimate kingdom, so, no doubt, as in Cole’s painting, there will be a need for soldiers—the glory of the noble warrior is also a subject of the lyric poem, a dream of the arcadian mood. Still, in my lyrical dream, it is largely a peaceful world—unstable perhaps, like Socrates’ “city for pigs” or Cole’s Arcadian State, but in itself lovely and worth pursuing and contemplating.

I have no practical way to bring about this vision, a vision that arises in my mind when I look at Cole’s paintings (or Poussin’s, or others’). I have no idea how we would get there. That’s not the point. The point is that the pastoral mood—a mood we can cultivate by contemplating the right poems and paintings and music—shows me that such a state is desirable, more than all the dreams of power and wealth, Christian or secular. It helps me realize that we don’t have to live the way we live now. We can live differently—more beautifully, more simply, more peacefully.

Thank you again Mark. I get where you are coming from. I often seem to have what I sort of think of as an Arcadian mood (for want of a better word) in the evening, at l'ora d'oro (the hour of gold) as the Italians say when the world seems transformed into something more golden, simple, enchanted and evocative. It feels like a kind of nostalgia for the way things maybe once were, and maybe should be. A time when it seems mallorn trees might be real.

One of my favourite literary evocations of this mood - and a very English evocation of just this kind of nostalgiac longing - was provided by the war poet Rupert Brooke at the end of The Old Vicarage Grantchester:

"... Ah God! to see the branches stir

Across the moon at Grantchester!

To smell the thrilling-sweet and rotten

Unforgettable, unforgotten

River-smell, and hear the breeze

Sobbing in the little trees.

Say, do the elm-clumps greatly stand

Still guardians of that holy land?

The chestnuts shade, in reverend dream,

The yet unacademic stream?

Is dawn a secret shy and cold

Anadyomene, silver-gold?

And sunset still a golden sea

From Haslingfield to Madingley?

And after, ere the night is born,

Do hares come out about the corn?

Oh, is the water sweet and cool,

Gentle and brown, above the pool?

And laughs the immortal river still

Under the mill, under the mill?"

Whether this England actually existed - or is known to the reader/listener to the poem - does not really matter. It's a deep evocation of an idealised vision of a mythical Arcadian Cambridgeshire that transports me, Australian that I am, to his world. That it comes as both a contrast from, and a tonic for, a very mortal place as the closing lines almost gut-punchingly make clear:

"Say, is there Beauty yet to find?

And Certainty? and Quiet kind?

Deep meadows yet, for to forget

The lies, and truths, and pain? . . . oh! yet

Stands the Church clock at ten to three?

And is there honey still for tea?"

All that is a long winded way that I have a strong natural inclination to agree with you at an almost visceral level about wanting to honour and maybe even cultivate this state. But then I would like to go into the heart of Lothlorien too ...

But then the more hard headed side of me also thinks that, like any mood, it can be seductive and quite dangerous if not held in the right way. It is always in danger of degenerating into crass sentimentality or at least self indulgent romantic longing. Perhaps even more dangerously the fact that the political is indeed always hovering in the background means it is both fragile and maybe even a trap. I don't know whether you have ever seen the 1986 movie The Mission. If not, you need to. It brilliantly contrasts an Arcadian ideal of what Christianity (in particularly a genuine Catholic sensibility) could and should be with real world politics and the pretty much inevitable compromises that almost always undermine any attempt to bring it about. Jeremy Irons' compellingly acted character the Jesuit missionary Father Gabriel really is a multi-dimensional ideal Catholic priest. The soundtrack is Ennio Morricone's masterpiece and the famous track "Gabriel's oboe" almost feels like a musical evocation of Arcadia (as do many of the other later tracks as the mission village comes into being). But then Cardinal Altimarano - not a bad man - is left haunted by the vision of what was achieved and then, in part by his hand and assent, wiped out including the death of Father Gabriel whose worth he knows. One message of the movie seems to be that any Arcadian reality will be fragile and will lose to realpolitik - Altimarano acted as he did in part because he thought the mission was going to be wiped out whatever he did. Which then leads to another troubling question about whether the mission - however beautiful - was really worth trying in the first place given that the death or enslavement of the natives seems almost inevitable in hindsight. Was their being shown the light a kind of cruel seduction? But then again, for a brief shining moment a vision of what could be, and maybe should be, came into existence and presumably has a value of its own?

Apologies again for this long comment. But you write about things that interest me. Please keep up the good work!